Summer 2023

Dr. Gregory S. Springer, Chair

Department of Geological Sciences

Ohio University

Athens, Ohio

Description

Science and an Accident in Fullers Cave

Fullers Cave is a tributary within the Culverson Creek Cave System, which consists of a 1.5-mile-long canyon that intersects the main Culverson Creek Cave trunk near the downstream terminus. Fullers drains Thorny Hollow and is notable for its dynamic flooding and unstable areas near its sinkhole entrance. My graduate students and I have been performing research in Fullers since 2018 concerning scallops, flooding, and sediment transport. A typical Fuller canyon passage is shown in a photo that accompanies this article. The Fullers stream is transporting large cobbles that are visible in the photo.

The scallop research indirectly led to a publication in the International Journal of Speleology with my former student Drew Hall (Springer and Hall, 2020), and the flooding research produced a paper in the same journal with Lydia Albright (Albright and Springer, 2022). Drew and Lydia were two of the best MS students I have worked with, and their results directly led to ongoing work in Fullers with my current student Sydney Hansen.

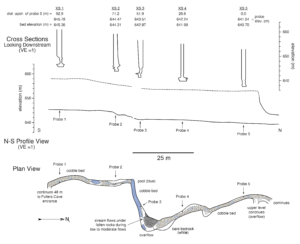

We are studying a 300-foot-long stretch of the Fullers canyon wherein we have placed probes to continuously monitor water levels. The reach is about 500 feet downstream of the Fullers sinkhole entrance. The canyon reach we are studying is shown in a figure that accompanies this article in both plan and profile views.

The water level data is combined with stream discharge measurements made outside of the cave to calculate a variety of things and to model flood flow. We use either an electromagnetic flow meter or the salt dilution method to determine discharge. The salt dilution method involves dumping a known quantity of salty water in floodwaters and measuring water conductivity downstream. The amount of dilution that occurs between where the salt solution was dumped, and conductivity is measured is used to calculate discharge.

The probes were purchased by Ohio University, but the conductivity probes for salt dilution measurements were purchased with grants from the Cave Conservancy of the Virginias (CCV) and the West Virginia Association for Cave Studies (WVACS). The CCV probe is also being used in Dry Cave. I note that we only use salt dilution during floods and the salty water is too diluted to hurt critters living in the stream.

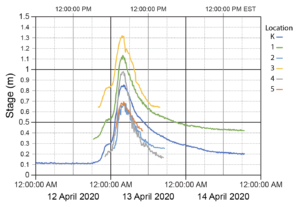

In total, we have five water level probes in the study reach (see map). They measure water level every 10 minutes and hydrographs are shown in another figure accompanying this article. Notable, the in-cave probes are only submerged during floods, so their hydrographs are blank until floodwaters reach them.

As you can see from the hydrographs, Fullers floods quickly, although the flood shown here is modest compared to those that fill the lower 20 feet of the canyon. Nonetheless, Lydia was able to determine water velocities during floods (~1.5 meters per second) and quantitatively determine the hydraulic roughness of the channel. Roughness is hard to measure, so our study is unique.

Sydney is modeling sediment transport in Fullers as part of her MS thesis. This entails modeling floods in the same canyon reach as Lydia, but Sydney’s model will incorporate movement of cobbles in the stream. Such studies are rare in caves, so her work will be as or more unique than Lydia’s.

In support of Sydney’s thesis, we spent a week in May collecting data in the cave. We were accompanied by field assistants Logan Leffler and Xandra Rowen. This article focuses on that fieldwork and a few results we have generated. Logan and Xandra are geology undergraduates who volunteered to help Sydney and proved invaluable.

Sydney had previously painted rocks in the Fullers stream to track sediment movement. The May work included measuring the dimensions of the painted rocks that moved and how far they traveled. We also emptied a sediment trap Sydney installed earlier in the year. The trap had filled with sediment, and we measured the total mass of sediments trapped and the dimensions of larger grains. The sediment measurements required a day of work, and the rest of the week was spent surveying.

Sydney, Logan, and Xandra found measuring the painted rocks quite the ordeal given that 108 rocks had moved, and each required three length measurements in addition to being weighed. Mind numbing is one way to describe the work. Of course, as Sydney’s advisor, I provided excellent supervision and religiously avoided directly getting involved. However, I didn’t escape unscathed.

The sediment trap was overflowing with water in addition to 200kg of sediments. Someone had to spend hours excavating the sediments so they could be weighed, and dimensions measured where necessary. Unfortunately, I was that someone. It was May, but that doesn’t mean the cave stream was warm! We made all the necessary measuremenrts, but we observed several deficiencies in the trap’s operation, so we ended up removing it later that week.

The surveys entail three separate activities. First, Sydney is surveying the canyon using typical caver methods, with the goal of producing a map like the one that accompanies this article. However, her map will start at the entrance and extend 1000 feet downstream. Second, a detailed profile of the streambed is being surveyed with measurements roughly every meter. Third, detailed cross sections are being measured in the study reach. All of this takes time, and we are not done yet.

Sydney, Xandra, and Logan began the traditional-style cave surveying on the last day of fieldwork. They continued downstream from the study reach, which I had previously surveyed to produce the map with this article. I typically train students to pursue necessary tasks but have them lead trips without me for reasons of professional and personal development. So, I did not accompany them on the survey, but checked on them later.

Sydney et al. drove to Fullers and got to work while I walked from WVACS to Fullers via the Buckeye and Williamsburg roads. They had my caving gear in the car, so I didn’t have to carry it on the walk in addition to my weighed hiking backpack. The walked proved to be 5.8 miles long and was very interesting. There were ample exposures of the Greenbrier limestones and colluvial and alluvial deposits in cutbanks of Buckeye Creek. I took a lot of pictures and made a variety of GPS way-points!

Eventually, I reached the car at Fullers and changed into my caving gear and headed to the cave to join the others. Here is where things got really interesting… There are three waterfalls between the Fullers sinkhole entrance and our study reach. I passed the first two without any problems, but after having been in Fullers dozens of times, I was being lackadaisical and not totally paying attention to what I was doing. Never take a cave for granted!

As I started the last climb-down, I misplaced my left foot and found myself falling down the 6-foot-high drop. My left arm had been braced against the wall as I placed my foot, so to keep from falling on the rocks below, I instinctively used my right leg to push my left side and arm against the wall.

I fell just enough for my left arm to be raised above my head, but I had to push so hard to my left that there was a LOUD pop in my left shoulder! And I mean loud. The pain was so intense that I don’t remember what happened next. I just remember ending up below the drop bent over in horrible pain. At first, I thought I had dislocated my shoulder, but I realized it was in the socket. So, either it popped out and back in, or something else had happened.

Despite the pain, I went downstream and found the others just as they finished their survey. I couldn’t lift my left arm, so I told them I was leaving, and, in fact, we all exited. That was the last day of fieldwork and a few days later the pain drove me to Urgent Care. An MRI showed my rotator cuff is torn in two places. An orthopedic surgeon would later tell me surgery probably wouldn’t help much, so we are in a wait and see situation.

Fortunately, I was later cleared to resume activities and told my main limitation would be pain tolerance. The arm is usable, but even with a cortisone shot it gets angry when I do certain things. Such is the price for not paying attention in a cave.

We will pursue more fieldwork in July and August. A lot surveying remains to be done, which is not difficult. Just time consuming. Eventually, the work will result in a thesis for Sydney and a publication. I can only hope her thesis’ acknowledgement section thanks my shoulder for taking one for the team. J

References

Albright, L., and Springer, G., 2022, Empirical roughness coefficients for moderate floods in an open conduit cave: Fullers stream canyon, Culverson Creek Cave System, West Virginia: International Journal of Speleology, v. 51, p. 123–132, doi: https://doi.org/10.5038/1827-806X.51.2.2436.

Springer, G., and Hall, A., 2020, Uncertainties associated with the use of erosional cave scallop lengths to calculate stream discharges: International Journal of Speleology, v. 49, p. 27–34, doi: https://doi.org/10.5038/1827-806X.49.1.2292.